RMS LUSITANIA

World War I started in July of 1914 between the Allies comprised of the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire and the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Later in the war, the U.S., Italy and Japan joined the Allies and the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers.

The people of the United States were not interested in joining the war. U.S. bankers and businessmen however, were making a sturdy profit from war bond trading and munitions sales. J.P. Morgan was brokering war bonds and making commissions on both the purchase and sale of them to finance the Allied cause. He had approximately $1.5 billion in loans out to France and England.

Morgan was also heavily invested in shipping lines including the British White Star Lines that were supplying the Allies with food and ammunition supplies. J.P. Morgan had much to lose if the Allies lost the war and defaulted on his loans, bonds, and shipping contracts.

The Germans had a fleet of Uboats that were sinking the supply ships for the Allies. There was an agreement called Cruiser Rules which allowed for the Uboat to surface, issue a warning to allow the passengers to escape to lifeboats, and then the Uboat would sink the ship. Winston Churchill who was the First Lord of the Admiralty issued orders to merchant ships to fire upon or ram the Uboats. This forced the Uboats to sink them without warning.

Churchill was desperate to have the U.S. join the Allies in the war. “The first countermove, made on my responsibility, was to deter the Germans from surface attack. The submerged U-boat had to rely increasingly on underwater attack and thus ran the greater risk of mistaking neutral for British ships and of drowning neutral crews and thus embroiling Germany with other Great Powers” The World Crisis by Winston Churchill. Churchill also ordered British ships to remove their names and when in port fly the flag of a neutral power, preferably the U.S. flag. Also the survivors of the U-boats “should be taken or shot-whichever is the most convenient” and “In all actions, white flags should be fired upon with promptitude.”

Just before the RMS Lusitania sailed in May, Churchill wrote this memo to Walter Runciman, president of Britain’s Board of Trade: “It is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany . . . . For our part we want the traffic — the more the better; and if some of it gets into trouble, better still.”

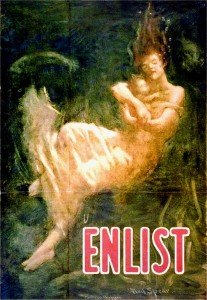

The German Embassy in the U.S. paid for an advertising warning in 50 U.S. papers in April 1915 that the Lusitania was at risk for destruction and travelers should embark at their own risk. The U.S. State Department intervened though and only one paper, the Des Moines Register ran the warning.

The Lusitania set sail for Liverpool on May 1st, 1915 from New York harbor. It was carrying millions of rounds of ammunition and shrapnel. The previous captain Daniel Dow had resigned because of mixing civilian passengers with munitions. The ship was to have a British battleship escort called the Juno but was recalled before the rendezvous in spite of the knowledge that a Uboat was active in the path of the Lusitania.

On May 5th, the Uboat U20 sank the schooner Earl of Lathom. On May 6th, it also sank two more ships, the Candidate and Centurion. All of these sinkings occurred directly in Lusitania’s course. The Lusitania was given orders under the premise of saving coal to only run 3 of 4 boilers which would slow the vessel considerably. The only warning Lusitania received was a general “submarines active off south coast of Ireland”.

At about 2:10 pm on May 7th the Lusitania was hit with a torpedo that had been fired by U20. Immediately following the explosion, a second explosion occurred. The ship sunk in 18 minutes. There were 1,959 people on board of which 1,198 died including 128 Americans.

Captain William Turner was blamed by the Admiralty in an official Board of Trade inquiry held by Lord Mersey. Captain Richard Webb of the navy wrote to Mersey: “I am directed by the board of Admiralty to inform you that it is considered politically expedient that Capt Turner, the master of the Lusitania, be most prominently blamed for the disaster.” Winston Churchill’s response to the report given to Mersey was “Fully concur! We shall pursue the Captain without check!” Luckily for Captain Turner, Lord Mersey was a fair man and saw that Turner was becoming the scapegoat. Turner was found not guilty and the German government was blamed. Mersey resighttp://falseflag.info/help/ned and called the trial “a damned, dirty business.”

The sinking of the Lusitania was a clear false flag perpetrated by Winston Churchill and the British Admiralty to draw America into the war. The blame should have been placed on Churchill’s orders and not the German government. It was probably no coincidence that the ship was owned by J.P. Morgan’s competition in shipping. The Lusitania sinking did not immediately draw the U.S. into war however, and it was almost two years later that the U.S. finally joined the war.

The U.S. has a big share of the blame as well. Colonel Edward M House who was Woodrow Wilson’s right hand adviser was in Europe trying test the waters on how to get the U.S. into the war. Wilson had to remain to appear as

anti-war since he ran on the 1916 presidential campaign slogan “He kept us out of war”.

Colonel House came up with a scheme to make it appear that the U.S was trying to broker peace with the Axis powers. The peace offering would be unacceptable to the Germans so it would seem as though the U.S. had attempted diplomacy. This is a memo from Walter Hines Page, the U.S. Ambassador to England, dated Feb. 9, 1916:

“House arrived from Berlin-Havre-Paris full of the idea of American intervention. First his plan was that he and I and a group of the British Cabinet (Grey, Asquith, Lloyd George, Reading, etc.) should at once work out a minimum programme of peace – the least that the Allies would accept, which, he assumed, would be unacceptable to the Germans; and that the President would take this programme and present it to both sides; the side that declined would be responsible for continuing the war… Of course, the fatal moral weakness of the foregoing scheme is that we should plunge into the War, not on the merits of the cause, but by a carefully sprung trick.” From The Strangest Friendship in History: Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House George S. Vierick.

Then this memo was issued by Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, on Feb. 22nd, 1916:

Colonel House told me that President Wilson was ready, on hearing from France and England that the moment was opportune, to propose that a Conference should be summoned to put an end to the war. Should the Allies accept this proposal, and should Germany refuse it, the United States would probably enter the war against Germany.

Colonel House expressed the opinion that, if such a Conference met, it would secure peace on terms not unfavourable to the Allies; and, if it failed to secure peace, the United States would leave the Conference as a belligerent on the side of the Allies, if Germany was unreasonable.

Colonel House expressed an opinion decidedly favourable to the restoration of Belgium, the transfer of Alsace and Lorraine to France, and the acquisition by Russia of an outlet to the sea, though he thought that the loss of territory incurred by Germany in one place would have to be compensated to her by concessions to her in other places outside Europe.

If the Allies delayed accepting the offer of President Wilson, and if, later on, the course of the war was so unfavourable to them that the intervention of the United States would not be effective, the United States would probably disinterest themselves in Europe and look to their own protection in their own way.

I said that I felt the statement, coming from the President of the United States, to be a matter of such importance that I must inform the Prime Minister and my colleagues; but that I could say nothing until it had received their consideration.

The British Government could, under no circumstances accept or make any proposal except in consultation and agreement with the Allies…

(Initialled ‘E.G.’ by Sir Edward Grey) Foreign Office.

Wilson also had an agenda to bring in his vision of world government under the League of Nations and saw World War I as his opportunity to do so. The plans of Churchill, Wilson, Morgan, and House to get the U.S. involved in the war came to fruition on April 16, 1917 when the U.S. formally declared war.